Bloom filters in Ruby

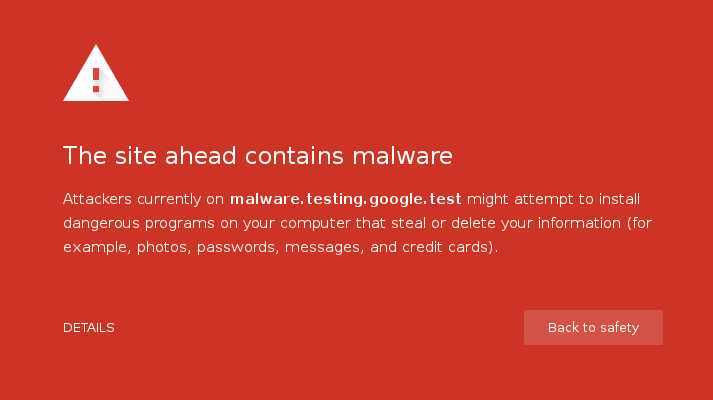

It is known that multiple dangers lurk in depths of the Internet. Anyone could easily fall victim to a malicious site with a simple web search or clicking aimlessly at any link we find in the way. But in Google Chrome, before you enter any malicious site you get the following warning:

This works pretty well as a prevention method, saving the user from a possible infection. But, how does Chrome really know that this particular site is evil? One possible answer is that the browser is keeping stored in some database a lot of URLs corresponding to the malicious sites. Furthermore this has to be done locally, because we do not want to waste time sending a request to a Google server every time we visit a webpage. But saving all this data locally wouldn’t take lots of space in disk? Then, how do they do this efficiently? The answer is using a special data structure called Bloom Filters. Chrome uses this data structure to solve this problem, as well as Bitcoin, Cassandra, BigTable and others do.

So we need Bloom Filters…

Bloom Filters? What’s that about? A Bloom Filter is a probabilistic data structure that can answer if a particular element is contained within a set. This is done fast and efficiently, requiring few memory. The trick to achieve this relies in its probabilistic nature. The data structure is probabilistic in the sense that we can find false positives in some of our queries. This means that for some query, it can return true (with some probability) for an element that is really not in the set. But in our malware example and many other applications, it is acceptable to have false positives if it means to have a fast and low cost solution. We could find a website erroneously marked as malicious, but we’ll see later that this is not common.

At first glance, it seems to be a hard structure to implement but in fact it’s really easy. We’ll code a Bloom Filter easily using plain Ruby. Our Bloom Filter is based on Bitfields: simple arrays of zeros and ones, stored directly in binary format. This is the secret to achive a low memory usage, each byte can hold eight elements of the Bitfield. The Bloom Filter has two main functions: add an element and search for an element. To add an element to the structure certain bits are set to one, and when searching for that element, it checks if those same bits are set. To achieve this, we must take care to hash each element appropriately. And that’s it.

This implies several things. We are not actually saving the element with all its information (an URL in our example), but only its hash. So, we can only ask if an element is included or not within the set, but we cannot retrieve information about those elements. This also means that we can’t ask the structure to give us a list of the elements already included in the set. If we examine the Bloom Filter that Chrome uses, we couldn’t know which malicious URLs are included. We also don’t have a delete method, this is another disadvantage of the structure. It is up to the programmer and the nature of the problem he has to solve if these disadvantages are acceptable or not.

Coding time!

To implement this on Ruby I used a Bitfield that I found here (credits to the original author). Having that part already solved, let’s start with the Bloom Filter per se. First of all, how do we know if our structure is empty? That’s easy, if I add any element then there will be some bit set to 1. If I didn’t add anything to the filter, all bits are 0:

def empty?

is_empty = true

@filter.each{|bit| is_empty &= (bit == 0)}

is_empty

endBefore looking into the add and search methods, I need to know how to hash elements. It’s simple in Ruby:

def hashes(elem)

hash = Digest::MD5.hexdigest(elem)

[hash[0..8],hash[9..16],hash[17..24], hash[24..32]]

endI use MD5 to hash, and then I split the result in four parts. MD5 is used just as an example, because this is only a toy implementation. MD5 is slower than necessary for this structure, there are other hash functions more convenient for this application like the murmur hash. I’m also splitting the result in four parts, each part will set a different bit in our bitfield. I use four parts, but it could be more or it could be less. Changing the number of parts will affect the number of bits set in each operation and ultimately, the false positive probability.

We can now have an add method. To add a new element we first hash it, and for each of the parts of that resulting hash, we set a bit on the bitfield:

def add(elem)

hashes(elem).each {|hash|

@filter[hash.to_i(16) % @filter_size] = 1

}

endTo query, we repeat the procedure. We hash the element, and for each part, we check if that bit is set to 1:

def query(elem)

hash = hashes(elem)

is_elem = true

hashes(elem).each {|hash|

is_elem &= (@filter[hash.to_i(16) % @filter_size] == 1)

}

return is_elem

endNote that some hashes can collide and try to set a bit that is already set to 1 by other elements. This is where the false positives come from, several elements can have the same hash. If I ask for an element that is really not in my filter, it can happen that other elements already set those bits to 1. So the query method will return that my element is included in the set when it really shouldn’t. A curious fact resulting from this: if all bits in my filter are set, it will return true for absolutely all elements possible in the universe. If my URL Bloom Filter is full, I will find an apple or a car if I hash them.

Luckily, we have a formula to know approximately how many elements the bloom filter has:

def approx_size

n = @filter_size

x = @filter.to_s.count '1'

k = 4

-n * Math.log(1- x.to_f/n) / k

endWhere n is the size of my bloom filter, x is the number of bits set to one and k is the number of hashes (that, in our case, is 4). Doing a couple of tests it ends up being surprisingly precise.

Again, this is only a toy implementation, not suitable for a production environment, but I hope you liked it.